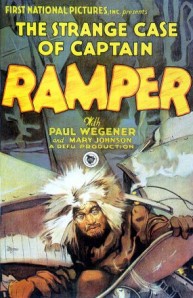

There are many ‘lost’ Cine du Sasquatch movies (some will be profiled on this blog and many more in my forthcoming book The Bigfoot Filmography from McFarland in the Fall of 2011), but perhaps none so obscure as Ramper, der Tiermensch [aka Ramper, the Beastman], or as it was generally titled to English-speaking audience of the 1920s, The Strange Case of Captain Ramper (1927). The odd but intriguing fact that two of German silent cinema’s great talents – director Paul Wegener known perhaps most famously for his Golem films and actor Max Schreck inevitably for his iconic portrayal of Count Orlok the vampire in the Murnau’s Nosferatu – appear in Captain Ramper make it one for the head-scratching puzzle records that the final film is so relatively forgotten, especially by Bigfoot cinema fans.

Captain Ramper (played by Wegener) — a famous explorer who was once thought lost in the icy north prior to his rescue years later when Ramper has become in effect a human primitive — is always shown to be the implied Yeti in question throughout The Strange Case of Captain Ramper. In other words, the film’s point of view is such that the human observers are the ones projecting their belief Captain Ramper himself is the Abominable Snowman atop Ramper’s mute, non-protesting silence. How else to explain the tall, fur-covered “wild man” the curious crew recover in the Arctic wastelands? Appropriate to the title, this is a strange inversion of the usual “man in an ape suit” motif in which a supposedly legit Sasquatch is revealed as a hoax by the conclusion; whereas, Ramper in The Strange Case of Captain Ramper is the “ape in a man suit” reversal, with the Yeti a case of mistaken identity.

Ironically, humanity itself becomes a questionable commodity which is arbitrarily given and taken away by Ramper’s fellow human beings (at least from Ramper’s point of view, which is largely the film’s p.o.v., as well). The delicate European society of The Strange Case of Captain Ramper of genteel well-doers and bourgeois shop owner types have no use for a once famous exploratory Captain who is already historically forgotten to them, let alone a mute “Ice Man” who seemingly lacks even rudimentary intelligence or proper esteem for such truly important skills as pinkie extension during high tea. In essence, Ramper as Yeti is excluded not because he is a Yeti, but because, sadly, no longer is mere physical resemblance the only criterion by which impatient human beings may collectively revoke another individual’s status. The tribe bestoweth the title of “fellow human” and the tribe revoketh.

As The Strange Case of Captain Ramper shows in an eerie tonal prefiguring of The Elephant Man, even a genuine specimen of Homo sapien stock can be reduced to less than human if the perception by the mass around him suggests that said subject is somehow inferior or lacking in the “good genes” of the human DNA genome. In this sense, we glimpse the underlying roots of racism, class divisions, uber nationalism, and many other inherent social ills; our own biased nature works to insure these moral failings as a steady-stream by-product of our ongoing, largely chaotic creation of a civilized society. That the decision to reduce Ramper from exploration demigod to sub-humanoid in status is largely arbitrarily-made, outside Ramper’s control, without any critical debate at all by the human participants is grotesque in the same vein as the aforementioned The Elephant Man or Browning’s Freaks. It suggests the cruel nature humanity is capable of invoking to exclude its own for the most superficial of reasons, even as it creates societal structures to reward more fame and riches to those who already have plenty.

The inability of society to tolerate noncomformity -- even when heroically achieved -- is a key theme.

Indeed, it is as if we are witness to a pagan ritual in which the crowd is chanting for more sacrifice at whatever cost, offering up burnt embers of self-destruction, and never once seeing that their actions are ultimately short-sighted with tragic consequences soon to follow. Into this scenario, Ramper reveals the perfect wrecked psyche for which the ever-fascinated public to consume upon and vicariously live through (at least, that is, until the next diverting thrill comes along), as – not unlike John Merrick’s own historical case in point – Ramper is an ongoing transformation in life, offering multiple levels of “viewer” empathy, interest, and exploitation. Ironically, the whole of Ramper’s life has been to become trapped like Prometheus in a series of scene-stealing tableaux (first, the living icon of explorer and aviator; later, as the frozen man unable to muster an emotional response in the modern world). Beyond these two moments in time, it is as if Ramper the man never existed, nor ever will. It’s quite a bitter wind that blows throughout the soul and imagery of Captain Ramper.

The cast and crew are excellent. Known mainly as an actor from his series of German films featuring the Golem character during the silent era, Paul Wegener was a key player in the Expressionist tendency in German filmmaking circa the 1920s, also writing, directing, and producing movies. Max Schreck, the memorable Count Orlok from the original Nosferatu, here has a dual role, one minor and one major: as a sailor aboard the rescue vessel, Schreck is a crowd player who blends in as directed; as the embodiment of a series of horrors that befall Ramper during his 15-year long ordeal of estrangement, Schreck plays a series of representative woes such as Cold, Loneliness, etc. The latter sequence is the most Expressionistic of the entire film, using near-operatic intensity to suggest states of mental being (and non-being) with Schreck tormenting Ramper, year after desolate year, like some kind of demonic ice harpy, placed to do so by some truly angry Teutonic gods.

Excerpt from The Bigfoot Filmography forthcoming from McFarland.

Leave a comment